A deep dive on Bitcoin's flaws and how to fix them

Breaking down Bitcoin's issues and looking into how other cryptocurrencies have improved.

In these articles I often criticise Bitcoin for being too flawed for the long haul. I do this not out of malice, but because I want the world to have sound money. We don’t get to sound money by ignoring flaws. Bitcoin was not started as a final version of what crypto could look like, and Satoshi famously saw Bitcoin as a V0 rather than a final version. So today, I'm breaking down BTC's issues and exploring how other projects address them.

Our perfect cryptocurrency, similar to Bitcoin's aims, needs to be a medium of exchange and a store of value. There is interplay between the two. This store of value needs:

Uncensorability

Certainty of supply

Transferability

In crypto, 1) and 2) are largely a result of decentralization, as opposed to for example in gold.

Transferability refers to a store of value only storing value if you can retrieve the value later, for which it needs to be exchangable into other goods, assets, or services.

A first main concern with Bitcoin is uncensorability and certainty of supply, more broadly speaking security or decentralization. On this subject, there are two main worries for Bitcoin:

Decreasing security spend

Centralization of hashrate

Decreasing security spend

1) decreasing security spend is an attack vector. While hashrate might be going up, the metric that matters is the money spent on securing the network as a percentage of the market capitalization.

Security spend determines how difficult it is to 51% attack the chain, while the market capitalization determines the potential profit to be made in attacking the chain through opening a short position. The combination of the two determines how likely or attractive an attack is. Put another way, a $100 vault might be good enough to secure $1,000 in valuables, but would you trust that same $100 vault to secure $100,000?

The reason security spend is going down is that block rewards are decreasing. Every 4 years the number of BTC rewarded for a mined block halves. The current reward is 6.25 BTC per block (annual inflation of 1.7%), after the next halving in 2024 this becomes 3.125 BTC per block and inflation falls to 0.9%.

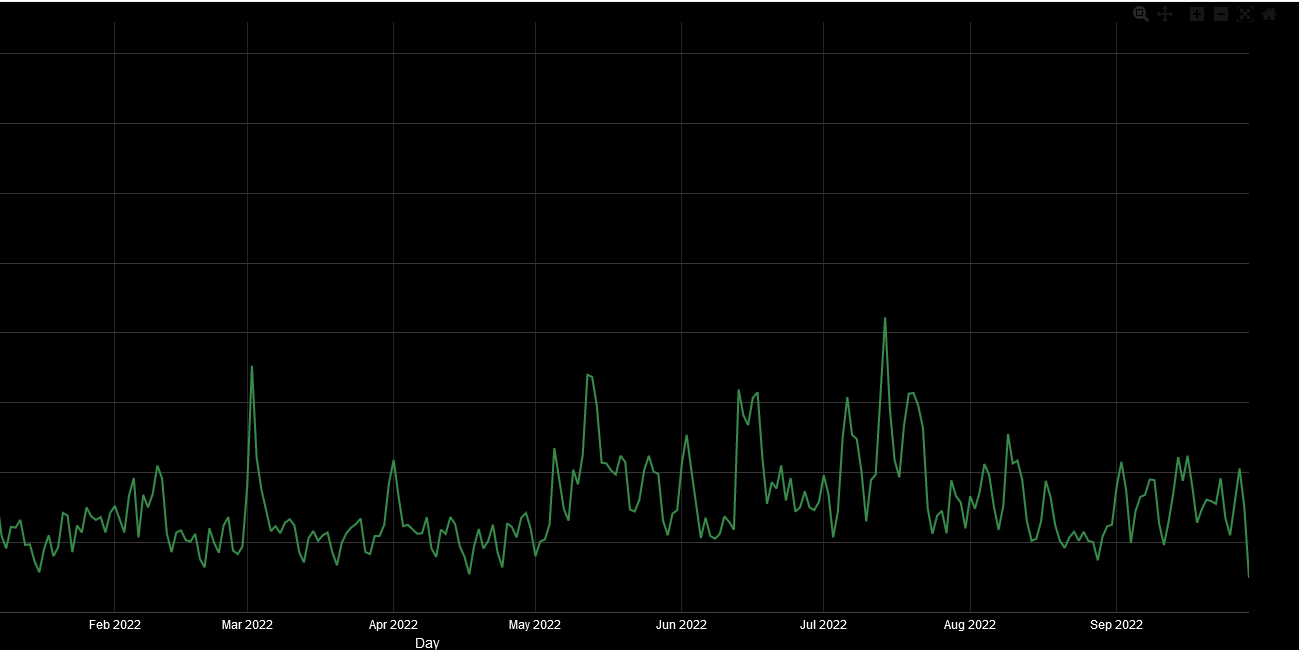

Unfortunately, 14 years in, transaction fees have not been able to pick up the slack from decreasing block subsidies, nor does there seem to be any sort of positive trend.

This makes sense. The higher fees get, the less usable the chain is. I might be okay using Bitcoin to transact with $1 fees, but I certainly don’t have many transactions I would want to do if I had to pay a $100 transaction fee for each transaction.

Concern 1) surrounding security, and it's a huge concern, is therefore that the potential profit to be made in opening a short and performing a 51% attack on Bitcoin keeps increasing. For more reading, I've written on this before.

The fact that such an attack has not happened yet does not mean much. There is a tipping point at which the attack will become profitable and attractive enough to do so. By the time that happens, it is too late already.

It is possible to (partially) fix this through a tail emission, where supply is no longer fixed at 21m Bitcoin maximum but increases with 2% per year.

Bitcoin maximalism and a potential tail emission

What is a tail emission? Certain cryptocurrencies such as Monero and Dogecoin don't have a fixed supply but perpetually reward an X amount of newly created tokens to block validators. This as opposed to Bitcoin, where there is a clear limit of 21 mln Bitcoin that will be issued in total. Bitcoin enthusiasts often mention this as a strong point for Bitcoi…

A tail emission obviously has an important trade-off, increasing security at the cost of Bitcoin’s store of value properties. Rather than boasting fixed supply, Bitcoin would have annual debasement built in moreso than it does today.

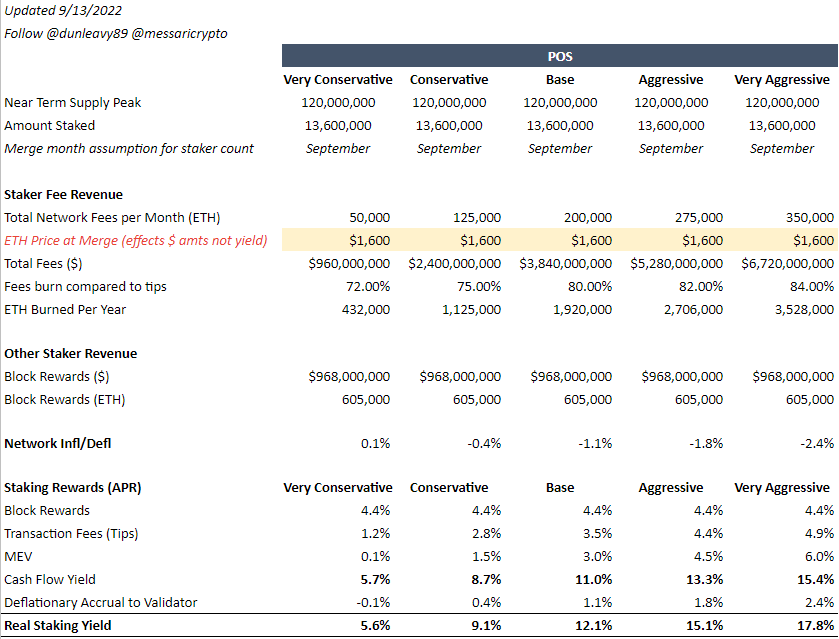

Other coins solve security in different ways. In Ethereum opening a short and performing a 51% attack does not make sense, as Ethereum’s Proof of Stake consensus mechanism means you effectively need to hold the coin to be able to attack it, making a short far less profitable.

A fork like BCH suffers from Bitcoin's problem as well. The BCH community would argue BCH can rely more on fee income, as the chain is both more usable (lower fees) and more scalable (32mb BCH blocks vs 1mb BTC blocks). However, if we swap out BTC for BCH and would want to replace half of the current block subsidy with fee income, this would mean requiring $15mln in daily fee income. At 1 cent per transaction this means a whopping 1.5bln transactions per day or 17,000 transactions per second. Blocks would need to be about 3GB, rather than the current 32MB. Possibly in the future, but it seems like wishful thinking for now.

Nano solves this problem in a similar way to ETH. To participate in consensus, you effectively need to hold the coin. Attacking the chain would mean attacking your own holdings, an unappealing proposition. An entity could try to attack the network by getting a majority of the stake. This would already cost many billions to do, and becomes more expensive with an increasing market cap. Additionally, anyone doing so would be essentially burning their own money.

Monero has a tail emission (a fixed emission rate), choosing to make the trade-off discussed earlier for Bitcoin. This provides 0.3 XMR per minute or 432 XMR (~$72k) per day, a roughly 0.89% inflation rate. Fees are just $1450 per day at the moment. Annual security spend as a % of market cap for XMR is roughly $26 mln on a market cap of $3 bln, or 0.9% compared to Bitcoin’s current 1.7%. In other words, XMR does not do better than Bitcoin on this aspect.

Concluding on security spend, it appears no Proof of Work coin has sufficiently solved this, it is already a vulnerability for Bitcoin, and becomes an increasingly big vulnerability. Coins such as ETH and Nano have solved this by moving away from Proof of Work to a system where consensus depends on coins rather than an outside resource, thus requiring investment into the system to be able to attack the system. This seems a better solution.

Centralization over time

2) A second worry regarding security is centralization of hashrate (consensus power, attack power) over time. This is, in a way, related to the security spend argument. The fewer miners you need to convince/bribe/hack to be able to 51% attack, the easier it is to attack the chain. The lower that mining revenue is, the more likely/cheaper it will be to bribe miners, etc.

However, centralization of hashrate is risky in other ways. Bitcoin is a store of value thanks to its decentralization. A system in which one entity can censor transactions or act maliciously to the detriment of other participants is a system we already know as central banking. Requiring 2 entities to perform a doublespend is better, but ideally we would prefer for it to be far more, and for that number (also known as the Nakamoto Coefficient) to be steady or increasing over time.

Bitcoin’s incentives do not lead to an increasing Nakamoto Coefficient. On the contrary, mining offers monetary rewards (block subsidy + fees). The more hashrate you have, the higher your rewards are. Bitcoin mining as a business focuses primarily on cost efficiency, as the revenue side (depending on BTC price + fees paid) is hard to influence.

Costs consist of energy costs, ASIC purchases and writedowns, capital costs, rent of server locations, maintenance, etc. Almost all of these costs have economies of scale associated with them. Large miners have stronger negotiating power with ASIC manufacturers, with energy suppliers (or can source their own energy), and can access capital more cheaply thanks to their size. They have lower average maintenance/upkeep costs for their ASICs. These economies of scale all combine and strenghten each other.

Combining mining rewards with economies of scale for mining leads to centralization of hashrate over time. The largest miners have the lowest cost-base, make the most profit, are able to reinvest most in ASICs, increasing their share of consensus over time.

The theory on it is quite clear, and research backs this up. See for example Miner Collusion and the BitCoin Protocol, Centralisation in Bitcoin Mining: A Data-Driven Investigation, Trend of centralization in Bitcoin's distributed network, Decentralization in Bitcoin and Ethereum Networks, A Deep Dive into Bitcoin Mining Pools, and Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market.

Note that this does not concern mining pools. While mining pools have different risks associated with them that deserve an article of their own, the more important risk is the centralization trend in individual miners.

Nodes play no role in solving this, everything that is being described here is within the rules of the protocol. Furthermore, nodes are vulnerable to Sybil attacks, which is why Bitcoin has Proof of Work in the first place.

The CPU power proof-of-work vote must have the final say. The only way for everyone to stay on the same page is to believe that the longest chain is always the valid one, no matter what - Satoshi Nakamoto

A decreasing Nakamoto Coefficient means decreasing security. It means decreasing value of the network - your store of value is more likely to be censored, the chain can be more easily attacked, certainty is being lost.

Unlike the security spend argument, ETH also suffers from this issue in a different yet similar way. The largest stakers have the highest ROI, smaller stakers have a lower ROI, while many don’t even stake, subsidising the big stakers even more. For more, see the article below.

Proof of Stake is a regressive capital tax system

In ETH’s Proof of Stake most people feel like they’re profiting, but the majority are losing money over time. Those that hold a lot of ETH are able to get maximum rewards, while the 99% that don’t stake lose out and subsidise these large holders. Those that fall in between do better than the non-stakers, but still lose out versus the richer ones.

BCH is no different from BTC here. The hash algorithm is the same, the incentives are the same, and the changes in terms of block size do not materially impact any of this. Monetary incentives drive miners to want to keep growing, and mining has economies of scale.

Nano solves this problem by removing monetary incentives and by linking validation to having funds in the network. Validators run nodes not for monetary incentives, but (much like non-mining nodes in Bitcoin) as an exchange to verify deposits, as a business to verify payments. Holders run nodes to secure their own holdings, wallets to run their service. In a broader sense, holders of Nano or users of the network derive value from the network, providing an incentive to maintain the network.

Rather than wanting to grow bigger and extract more money, validators want a high/increasing Nakamoto Coefficient as this maximises the value of their holdings. Small holders that do not run their own node use their Nano to vote for other nodes/validators, where 1 Nano = 1 vote. They are incentivized to vote in a way that maximises the value of their Nano by voting for smaller validators, increasing decentralization of the network.

Monero’s centralization trend is broadly similar to BTC and BCH, with one important difference. Whereas BTC’s hash algorithm (SHA-256) offers strong economies of scale, Monero’s RandomX was chosen to discourage use of specialized machinery like ASICs. This means that while the incentives to attain an ever large share of rewards are still there, it is far harder to do so. The economies of scale are far smaller than they are in BTC/BCH, though it has to be said that this offers different risks as the pool of available non-specialized hashrate is relatively large, offering potential for an attack.

Concluding on centralization of consensus power, this centralization over time is inherent to all PoW and PoS coins to a lesser or greater extent. Monero has minimized this trend within the PoW framework, while Nano flips the thinking by removing monetary rewards and actively incentivizing decentralization instead.

Concerns about security and decentralization are key to store of value properties. A decentralized form of money can only be a store of value with sufficient decentralization and resilience to attacks. Not just now, and not just because “it hasn’t happened yet”, but far into the future as well.

If we know an asset will become worthless in 20 years, we’d want to sell it before those 20 years are up. Others will want to do so as well, and sell before we have sold. Run this through to its conclusion and such an asset will be worthless very soon.

Medium of exchange characteristics

Aside from security through decentralization, a store of value needs transferability, or more broadly speaking medium of exchange properties. Something only stores value if we can retrieve it.

We could store our gold safely by shooting it out into space, but retrieving it to exchange it into goods or services would be difficult. Similarly, if we had a store of value where we were charged $100 to retrieve value we had locked into it, we’d have to take into account that we’re not storing $1000 but rather $900. Instead, we’d ideally want our store of value to be accessible easily, cheaply, and instantly.

Bitcoin presents three main worries in this regard, and they are related to each other:

Affordability

Speed

Scalability

Affordability

On 1) affordability we’re oddly at odds with the store of value arguments. In Bitcoin, affordability of transactions and security are inversely related. While high fees would mean a more secure chain, it also means that we lose value when retrieving our store of value.

Most see Bitcoin as a form of digital gold. Using it for daily transactions is largely out of the question already with $1+ fees. That then means that we have to wonder how often we want to access and retrieve from our store of value. When we are paid in Bitcoin, the sender has to pay a fee, eating into our store of value. We then presumably store most of the received money in Bitcoin, and perhaps use another, cheaper payment network to transact?

In such a case, we have to swap at least once, and have to decide how much money to keep in the cheaper payment network that is supposedly less secure and less hard. This presents a trade-off, where the less value we want to keep in the presumably cheaper payment network, the more often we have to swap back and forth, incurring costs every time.

With a $1 cost this is already painful for most. However, it gets worse in two aspects.

A $1 cost already means a lot to those that would benefit most from a strong store of value. Lower-income countries, where people suffer most from weak fiat currencies, would not be happy paying a $1 fee every time. To avoid this, they would likely have to use custodial options or give up control somehow, and lose many of the benefits of having a decentralized and uncensorable currency.

Perhaps more importantly, a $1 fee is unrealistically optimistic when we think of using Bitcoin at any sort of scale. With Bitcoin able to handle roughly 600k transactions per day, it is more likely that if many people start wanting to use it, fees would be higher.

There would be an equilibrium where many are priced out of using it at all. If fees are low, there's no security. If fees are high, the chain is hardly usable.

This links into the security budget discussion. Many people might want to use Bitcoin with $0.01 fees, perhaps 10% of those would use it at $1 fees, 10% of that subset at $10 fees, and so on.

The increasing fees with increasing usage are in many ways a self-defeating mechanism, where usability and medium of exchange properties deteriorate exponentially with increasing demand. Bitcoin proponents would argue that Lightning solves this. However, Lightning is not a good solution at all. It is fundamentally inefficient, doesn’t scale, is insecure and has terrible UX. See this thread for a deeper dive into LN’s problems.

Affordability within BCH is far better. Because block size is 32mb rather than 1mb, fees on BCH are generally just 1 cent or so, and this is unlikely to change. The mantra within BCH is to increase block size as necessary to keep it usable as money.

Ethereum has its own affordability problems, similar to Bitcoin in many ways. Although Ethereum is slightly more scalable, demand for blockspace is larger and fees on average are and have been higher. Ethereum looks towards further scalability on the base layer and through L2 solutions, but so far this is far from a full solution.

Nano is feeless, and does not suffer from the affordability problem. It’s designed around lack of monetary rewards for security and decentralization purposes. Regardless of the amount of transactions done or of future growth in price and transactions, fees simply do not exist in the protocol. Rather than prioritizing transactions based on how much is being paid in fees, transactions are prioritized by a combination of account balances and time. In short, despite not having fees, it is difficult to successfully spam Nano.

Monero is similar to BCH in that it is focused on low fees within a Proof of Work protocol. Fees are around 1 cent, and this is, like in BCH, unlikely to change.

Summarizing, affordability is worst in BTC and ETH ($1+), orders of magnitude better in BCH and XMR ($0.01), and best in Nano ($0).

Speed

2) Speed, or the time it takes to settle transactions, is not great in Bitcoin. This matters for a store of value less so if you are only using it every once in a while, but ideally we would like to be able to use our store of value to purchase goods and services directly.

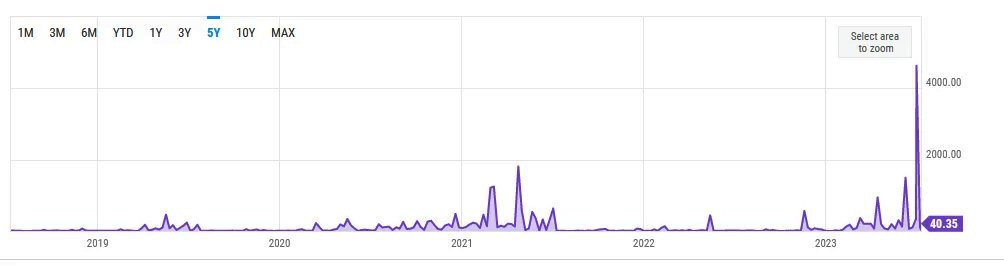

In BTC’s case, average confirmation time hovers around 40 minutes to be included in a block, then 60 more for it to be considered confirmed. With increased usage of the network and more congestion, this strongly increases, having spiked at 4000 minutes (2.5 days) recently.

To decrease our personal confirmation time, we would have to increase fees paid, further eroding the value of our store of value. Additionally, in that case we’re simply pushing others to the back of the queue. The often-heard claim that Lightning solves these issues is irrelevant for the aforementioned reasons.

BCH has faster confirmation times, though with a caveat. Many merchants will accept 0-conf transactions, transactions that have been picked up by nodes but have not been processed in blocks yet. In such a case, transactions can be done nearly instantly, but are not actually confirmed yet.

Kraken, who are incentivized to only consider transactions complete when they are securely confirmed, see BCH transactions as confirmed after 15 blocks or ~2.5 hours (as opposed to 3 blocks for BTC, which can be anywhere from 40 to 4000 minutes).

Using the same metric, Ethereum takes roughly 14 minutes to confirm. Similar to Bitcoin, scalability is limited and there have been periods where transactions took far longer to confirm. Also similar to Bitcoin, there are second layer options available, though those have trade-offs that I won’t go into right now.

Nano’s confirmation time is consistently sub-second, with averages hovering around 400 milliseconds. Using the same Kraken metric, the confirmation time is “near-instant”. Nano manages this because one transaction is one block. These blocks are broadcast to the network immediately, and voted on by all validators. When majority consensus (67%) is reached, the transaction is confirmed, cemented, and added to the chain. If the network is forced to process more transactions than it can handle, confirmation times would go up, though as mentioned before spam resistance means real transactions would be prioritised.

Monero is pegged at ~30 minutes on Kraken, though many enthusiasts would argue fewer confirmations are needed. Blocks are created every 2 minutes, and after a few (15, for Kraken) blocks have been built on top of the transaction the transaction is considered irreversible.

For a store of value, the exact confirmation time/speed matters less. As long as it’s not extremely long, as it has arguably sometimes been for Bitcoin and Ethereum under load, it’s fine. However, the more often you want to swap into and out of a store of value, the more important it becomes.

Ideally, we would like to have a store of value that we can directly exchange for goods and services. This would remove the friction associated with swapping back and forth, increasing efficiency. For such purposes, speed and confirmation times become far more important, and Bitcoin falls far more out of favor.

Scalability

3) Scalability is important for a store of value and medium of exchange both. In BTC, 600k people are able to do a single transaction every day. To scale to level where a large country, let alone most of the world can use the chain even as a store of value, more will be needed.

Outside of the aforementioned Lightning Network Bitcoin does not seem to have scaling plans. This leaves custodial options (banks, exchanges) which, while making exchanging easier, come with trade-offs in terms of censorability and remove many of the decentralization benefits.

Ethereum does slightly better in terms of scaling, being able to handle roughly 16 TPS rather than Bitcoin’s 7 TPS. The plan is to increase this further, while second layer solutions offer improvements at the cost of generally security and decentralization, or requiring fees to be paid to move into and out of sidechains. TPS improvements would have to be software-based for Ethereum, as it does not automatically scale with increases in hardware capacity.

BCH with their 32 MB blocks can do ~150 TPS. 256mb blocks are in the works which would allow it to scale further, and the idea is generally to keep increasing blocksize through software changes to keep sufficient capacity. For an interesting read on why BTC chose small blocks and BCH bigger blocks, “The Blocksize War” is a fascinating book. For now suffice it to say BCH scales better than Bitcoin.

Nano is currently able to do ~50 TPS. Unlike the aforementioned coins Nano does not require software changes to increase capacity. There are no inbuilt, protocol-level limitations to how many transactions can be validated per second. Instead, all nodes validate transactions as quickly and efficiently as possible. This means that if validators upgrade their hardware, max transactions per second increases. Many nodes nodes are currently run on cheap machines ($10-$30 a month). Since real usage is only 1-2 TPS at the moment, not more has been necessary. With increased adoption, max TPS would likely increase.

Monero, in a similar vein to Nano, has a dynamically adjusting blocksize. Current max TPS is unclear as actual TPS demand is low, but it should be roughly similar to that of BCH and Nano and more importantly keep increasing over time without requiring additional software changes.

In terms of scalability BTC seems to be a negative outlier, with BCH, Nano and Monero performing far better. To an extent, this seems an issue that is solvable in Bitcoin relatively easily, but as the Blocksize Wars illustrates Bitcoiners seem very unwilling to do so.

Summarizing, despite Bitcoin currently being the biggest crypto, it has a lot of problems. In terms of security and decentralization, the decreasing security budget leaves it increasingly open to attack, with no fix in sight. This is amplified by a decreasing Nakamoto Coefficient, making the chain less decentralized and therefore less secure.

ETH and Nano seem immune to the security budget problem, while only Nano and to an extent XMR seem likely to respectively increase or at least maintain their Nakamoto Coefficients, ensuring decentralization and security.

In terms of being a medium of exchange and to an extent playing into store of value characteristics, BTC has other issues. It is not affordable enough, less so with increasing demand, does not settle quickly or reliably, and does not scale, necessitating custodial solutions to remain usable even as a store of value.

Affordability is (largely) solved by BCH, Monero and Nano. These three also scale, Nano and Monero doing so even without further software changes. In terms of settlement speed, ETH and Monero settle far more quickly than BTC with BCH being more complicated. Nano is an outlier with instant confirmation, allowing not just use as a store of value but also as a direct medium of exchange, leading to full efficiency since there’s no need to swap back and forth.

Some of these problems in Bitcoin are solvable in theory (tail emission would help with security budget) but have serious trade-offs that make alternative currencies seem even more attractive.

Perhaps more importantly, Bitcoin is highly ossified in practice, with changes difficult to push through - let alone changes that would be the biggest changes Bitcoin has ever seen.

As other crypto projects have solved these issues to a greater (Nano) or lesser (XMR, BCH, ETH) extent, investors might instead prefer to vote with their feet, opting for harder stores of value, more secure forms of money, and more usable mediums of exchange. This is very much in line with the original thinking around Bitcoin, where rather than solving the problem from within (central banking), a better alternative was created.

We need to solve the majority if not all of these issues for BTC or any crypto to survive for the next 5, 50, 500 years, to move to having a true decentralized store of value and medium of exchange.

I’d urge anyone in crypto, either as an enthusiast or investor, to think these problems through for any coin you’re interested in, and to analyze alternatives this way. Subject coins to a harsh judgment. A high current market cap means nothing if security is unsustainable, current usage means nothing if scale can't be achieved, blind belief and “diamond hands” mean nothing if your chain becomes censorable.